Defined entity educational strategy for gender impact assessment

Author: Action for Gender Equality

Date: February 2022

A report by the Action for Gender Equality Partnership assessing the key barriers and enablers to advancing the work of gender impact assessments across Victorian public sector organisations, universities and local councils.

Acknowledgement

The Action for Gender Equality Partnership acknowledges the peoples of the Kulin Nation, the Traditional Owners of the land on which we work. We pay our respects to Elders past, present, and emerging. We affirm that sovereignty was never ceded, and that colonialism and racism continue to impact on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and can contribute to the high rates of violence they experience. We recognise the strength, resilience, and leadership of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and express our commitment to reconciliation.

Who is the Action for Gender Equality Partnership?

The Action for Gender Equality Partnership (AGEP) is a network of gender equity experts providing services in gender equity to the public, not-for-profit, and private sectors across Victoria. AGEP is state-wide, and the only provider of gender equity change that is place-based and regionalised. Members of AGEP deliver local and state-wide action for gender equality, tailored to all metropolitan and regional settings. In December 2021, AGEP successfully tendered to undertake a sector needs assessment and provide advice and recommendations to the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector (CGEPS) regarding how to strengthen its efficiency, effectiveness, and capability to meet emerging gender impact assessment (GIA) needs and deliver high quality advice to entities planning and undertaking GIAs.

Glossary of Terms

|

Term |

Definition |

|

AGEP |

Action for Gender Equality Partnership |

|

CGEPS or the Commission |

Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector |

|

D&I |

Diversity and inclusion |

|

GE Act |

Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) |

|

GEAP |

Gender Equality Action Plan |

|

GIA |

Gender impact assessment |

Citation

Action for Gender Equality Partnership (2022) Report for the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector: Defined entity educational strategy for gender impact assessments, AGEP, Melbourne.

Executive summary

The process to undertake a gender impact assessment (GIA) is one of four ‘foundation stones’ that the Victorian Gender Equality Act 2020 (GE Act) will deliver to achieve transformational outcomes for all Victorians. The other three are undertaking Gender Equality Action Plans (GEAPs), the positive duty to promote gender equality, and reporting on progress. However, all four must work in concert together.

The Action for Gender Equality Partnership (AGEP) worked from December 2021 to end January 2022 to engage with defined entities across the Victorian Public Sector to understand what key barriers and enablers there are to advancing the work of undertaking GIAs. The project heard some 497 points of view across survey, interviews, and focus groups.

It is evident there is a tension in the work currently underway to implement GIAs across defined entities. That is, implementation is consciously about encouraging and supporting defined entities to meet the regulatory requirement of GIAs, rather than an approach that would be more compliance-based. This report has found that while this approach does have a more sustainable outcome for systemic and structural capability, there are some capacity and capability realities that need to be addressed first.

This report provides information on the research undertaken for the project, the themes emerging, and puts forward some strategic observations on the characteristics of those defined entities that are successfully undertaking GIAs, and those that are not. It also puts forward a set of recommendations for CGEPS to consider and implement to respond to the themes in the feedback.

Impact of COVID – Resources pulled from GE Act work

Perhaps unsurprisingly for this moment in history, one key narrative in the report is the significant impact of COVID. Many workers who were implementing the GIA processes talked of being pulled off the GE Act work to other priorities. This was especially true for any respondent to this project in the health sector.

GIAs not resourced

A factor underpinning the feedback through this project is a lack of resources across defined entities to undertake GIA work. Consistently the authors heard about lack of time, lack of access to expertise, and lack of resources.

It was clear from the feedback across all sectors that many staff operate in a way that is a) isolated from business strategy (therefore missing out on GIA opportunities); and/or b) GIA activity is an add-on to a staff member’s ‘main job’; and/or c) GIA processes are occurring in a context where there is low organisational knowledge about GIAs and/or the benefits of gender equality.

Support for GIAs and the Commission

Given the challenges, it is important to note that there is broad, deep support for GIAs, and a significant sense of optimism about what GIA work can achieve. For many, GIAs are described as ground-breaking and critical to achieving intersectional gender equality across Victoria. There is also huge support and respect for the work of the Commission itself, and a desire to work more closely with the staff and team – the Commission staff are looked to as the key source of expertise on the GE Act and its obligations. Perhaps, driven by this significant support, the authors also heard an ‘anxiety’ to get GIAs done and right.

Overall, our recommendations conclude that:

- There is a need for additional support and guidance to enable defined entities to implement GIAs in their organisation.

- There is a significant number of defined entities that are disclosing a marked lack of organisational capability and readiness to implement GIAs.

- The barriers in place for implementing GIAs consistently include poor resourcing, poor access to expertise, and compounding time and resource pressures to the unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 pandemic health directions drawing those resources away from GE Act work.

- Defined entities and those leading GIA work are calling out for practical guidance and support on how to implement GIAs. Further to this, defined entities are seeking advice that is tailored to their specific region/geographical context and sector.

Action for Gender Equality Partnership

February 2022

Background

Context to the report

The project to undertake an educational needs analysis to assist defined entities to implement GIAs occurs at a critical time in the implementation of the GE Act and Victoria’s journey towards gender equality.

In the last 12 months, there have been key events and milestones that have framed the rationale for a gender-equal society. In addition to the commencement of the GE Act, the national context includes:

- Grace Tame named as 2021 Australian of the Year

- Ongoing work to implement the recommendations from the Australian Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins’s Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report

- The Australian Human Rights Commission launching Set the Standard: Report on the Independent Review into Commonwealth Parliamentary Workplaces.

The ongoing aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic reveals entrenched gender inequity across our society and economy. A 2021 report written by the Grattan Institute1 found:

- Women lost their jobs at a higher rate than men due to the gendered segregation of labour markets as people-facing industries are major employers of women.

- Women shouldered more of the unpaid care work, which was an increase over and above the heavier load that they already carry.

- “Women reduced their paid work and study, especially mothers… [with] single mothers ... yet to recover and ... among the most economically vulnerable.2

The pandemic has also disproportionately impacted women’s health and wellbeing. Nowhere is this more evident than the comparison between women’s and men’s mental health and wellbeing before and during the pandemic:3

- In 2020, an estimated 38 per cent of Victorian women reported having ever been diagnosed with depression or anxiety compared with 29 per cent of women in 2015.

- In 2020, an estimated 25 per cent of men reported having ever been diagnosed with depression or anxiety compared with 21 per cent of men in 2015.

The context is important for two key reasons:

- There is strong momentum across the Victorian Public Sector to advance gender equality and encourage leaders and workers to consciously notice inequality and norms, structures, and systems.

- It provides an environment for advocates and gender equality workers to increase the pace and energy in their work to deliver gender-equal workforces.

During this project, the AGEP project team heard resounding positive feedback about the GE Act and the value of GIAs. Many consultation participants had a deep understanding of why intersectional gender equality is of value to workers, organisations, and communities. This report posits that this positive regard is partly due to the introduction of the GE Act and the leadership of the Commission and the Victorian Government; but largely due to the reinforcing messages of gender equality that sit within the broader context of this work.

There is also a sense of urgency from consultation participants for support to enable the value of GIAs to be realised. This report describes a series of tensions, concerns, stresses, and threshold issues for the Commission’s consideration.

Brief of work

The Commission contracted AGEP to:

- Undertake and conduct sector consultation regarding the challenges and opportunities on GIAs and their implementation with:

- Commission staff

- Defined entities and other stakeholders

- Peak bodies as relevant

- Develop and deliver and insights report that:

- Defines the challenges and opportunities on implementing GIAs and the factors including but not limited to:

-

Challenges of embedding a GIA approach organisation-wide

-

How GIA support needs vary based on the sector and an organisation’s size and resourcing

-

How GIA support needs vary based on the scope and nature of the relevant policy, program, or service.

-

- Analyses current gaps in guidance, training, and advice

- Puts forward recommendations on additional guidance materials and education that meets the identified needs of defined entities.

- Defines the challenges and opportunities on implementing GIAs and the factors including but not limited to:

Methodology and approach

Introduction

The project team designed a consultation approach to answer the following high-level questions:

- Are defined entities implementing GIAs and to what extent?

- What is enabling implementation and what are the barriers to implementation?

- What additional support is needed?

The consultation was conducted over the month of January 2022. The consultation approach included:

- An online survey that was promoted through the Commission’s e-newsletter.

- Interviews with practitioners in defined entities that have experienced the challenges and opportunities of implementing GIAs.

- Focus groups with key stakeholders identified by the Commission and the project team as having the capacity to provide insights on GIA implementation.

Background and methodology framework

The methodology seeks to understand the enablers and barriers within the transformative foundations of the GE Act. The question design enabled the project team to understand the barriers and enablers to implementing GIAs within defined entities and the public sector more broadly.

GIAs ensure that programs, policies, and services are “responsive to the needs of all citizens”.4 GIAs are used across the world to shift the reality that policy, programs, and services delivered by organisations – be that private or public – are not ‘gender neutral’, but rather are the result and reflection of structural gender inequality present across our society. The obligations of the GE Act seek to redress the root causes of gender inequality and “make lasting and genuine progress towards gender equality across the community”.5 The GE Act seeks transformational intersectional gender equality and GIA is a tool in achieving this change.

Because the goal of the GE Act and its obligations – including the obligation to undertake GIAs – is to achieve transformative gender equality, it is important that the project methodology provides final recommendations that are calibrated against the evidence of what conditions are required to create such change.

Research and practice evidence shows that for transformative gender equality to occur, organisations, communities, and social structures need to have:

- Processes for change across the organisation that understand the biases and inequalities that exist already within the organisation7

- A readiness to proceed with structural and cultural change based upon building organisation-wide awareness, skills, and capability regarding gender inequality8

- Enacting organisational learning through ‘soft regulation’ within organisations to support the implementation of ‘hard regulation’ such as the GE Act.9

Perhaps the most significant driver of transformational gender equality within organisations is the role and capacity of leaders in as much as:

- the work to achieve genderequal organisations is a change process transforming systems and structures; and

- leaders have a vital role to play in setting the context, messaging, enabling resources for change, making congruent decisions, and role modelling the change that ‘we want to see'.10

The framework below aligns questions with the transformative practice required by the GE Act through GIAs, and possible indicators:

|

High- level question themes Levels of Investigation |

Current activity |

Enabler/Barrier |

Resources needed for GIA outcomes to be achieved |

|

High-level question |

Are defined entities implementing GIAs and to what extent? |

What is enabling implementation and what are the barriers to implementation? |

What additional support is needed? |

|

Underpinning questions informed by transformative gender equality practice |

Are GIAs occurring and at what volume and what scale? Are GIAs occurring on all new policies, programs, and services, as per Commission Guidance? Is the implementation of GIAs occurring in a way that is transformational? |

Are resources being provided? Are leaders driving change? What knowledge and capability do they have to drive change? Is there organisation-wide understanding of the role and value of intersectional gender equality? Are frontline workers who are doing GIAs supported or isolated? Are there existing structures and systems in place to support GIA activity? |

Are GIAs becoming business as usual (mainstream activity)? To achieve the (transformational) outcomes of the GE Act, is there alignment to the resources requested? |

|

Indicators/Evidence |

Implementation is occurring as per the requirements of the GE Act and its regulations, and is occurring in a way that is transformational. |

The level of resourcing provided for GIAs is inclusive of budget, time, and skills (change and intersectional gender equality). The extent to which leaders are driving implementation of GIAs and undertaking activities in line with driving transformational change. There is evidence reported of deliberate gender-equality capacity building across organisations. The extent to which systems and structures are in place that deliberately support implementation of GIAs and reflexively address inherent bias that may detract from gender-equal outcomes. |

|

Sector survey

An online sector survey was distributed by the Commission on 22 December 2021 through its sector e-newsletter. The survey was open from 22 December 2021 to 31 January 2022. The survey had eleven questions and targeted practitioners working in defined entities who were likely to be engaged in, and responsible for, undertaking GIAs. The survey was collected through a questionnaire application – SurveyMonkey. The full set of survey questions is detailed in Appendix One of this report.

Interviews

Five one-hour interviews occurred with stakeholders from the following sectors:

|

Stakeholder Sector |

|

Local Government |

|

Emergency Services |

|

Water Utility |

|

State Government Agency |

Interviews were structured around the following questions as per the above framework:

- What feedback are you receiving about GIA and what themes are you noticing around capacity, resourcing, and leadership?

- What does this mean for the resources and additional support required – now and into the future?

- How does GIA become business as usual?

- Is there an issue with the GIA process being implemented at scale – can it be implemented in small and large organisations?

Focus groups

Six focus groups with 162 participants were conducted with the following groups as detailed below. Focus groups went for 1.5 hours and were facilitated by the AGEP project team online. Focus groups were structured around the following questions as guided by the above framework:

- What GIA activity is occurring and what is working well and why?

- What barriers are there to GIA work not occurring or not occurring well?

- What opportunities are there to better support GIAs in organisations?

- Thinking more broadly, what environmental issues and other matters impact upon the completion of GIAs?

|

Focus groups |

Date |

|

Health |

27 January 2022 |

|

Rural Victoria, Sports and Recreation |

21 January 2022 |

|

Regional Local Government |

20 January 2022 |

|

Public Sector Diversity and Inclusion |

31 January 2022 |

|

Educational Institutions |

24 January 2022 |

|

Local Government |

31 January 2022 |

Focus groups and interviews were recorded for consultation purposes only and all participants were asked by AGEP for their permission to record the interview or focus group. Transcripts were generated through the Otter.ai platform. Thematic analysis of the data was undertaken, using an inductive approach to identify themes. The project team used Braun and Clarke’s seven step approach11 to:

- Independently familiarise themselves with the interviews and focus groups outputs

- Generate initial thoughts on themes emerging via a coding system

- Compare and search for themes (codes) across all interviews and focus groups

- Review themes for patterns and alignment to the project goals

- Produce a report on this analysis, which now informs this report.

Survey results

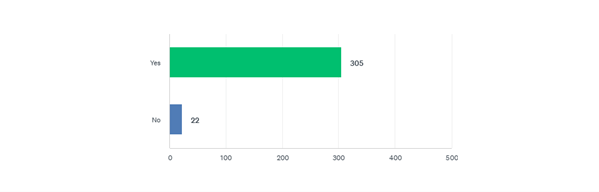

The online survey had 330 participant responses. Of these:

- 92 per cent (n=305) were from a defined entity

- 70 per cent (n=215) of practitioners from a defined entity reported that they had been or were involved in commencing a GIA

- 23 per cent (n=71) of practitioners from a defined entity reported that they were not currently or had not ever implemented a GIA

- 7 per cent (n=22) of respondents were not from a defined entity. These people were thanked for their interest and exited from the survey.

Survey structure

The survey was designed to elicit feedback from defined entities to understand from practitioners the barriers and enablers to implementing GIAs based on their experiences, as well as the reasons why some organisations are not implementing GIAs.

The categories of ‘defined entity currently or has been implementing a GIA’ or ‘defined entity not implementing a GIA’ were important in the survey design, as specific questions were designed for each cohort.

Characteristics of respondents

Ninety-three per cent of survey respondents were from a defined entity.

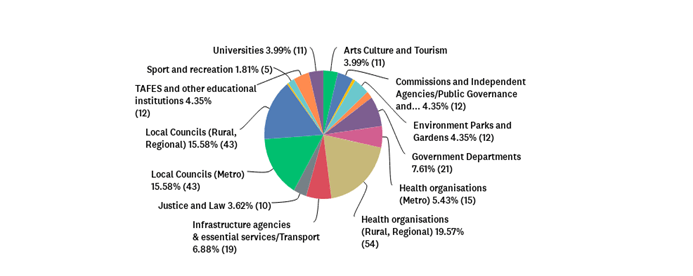

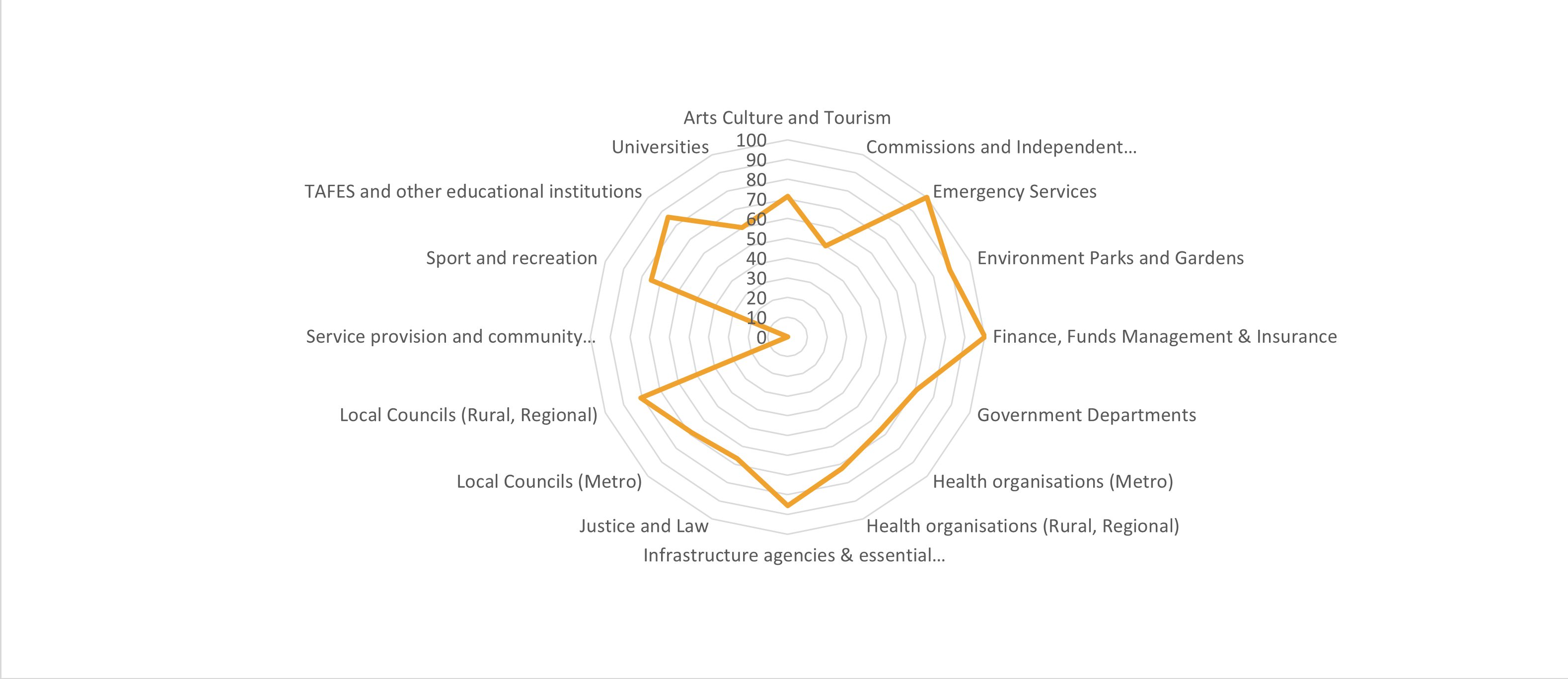

Figure two, as detailed below, shows that there were practitioners from a diverse range of defined entities who responded to the survey.

Questions for defined entities currently implementing GIAs

The survey asked specific questions of practitioners from defined entities that had experience implementing GIAs. This part of the report details their survey responses.

Organisational readiness and capability for GIAs

When asked what the level of readiness and capability the respondents currently believed their defined entity had to undertake GIAs in their workplace, a majority (73%) stated that their organisation had low capability and readiness. (**That is, they stated that their organisation was either "Not at all capable and ready", "Not so capable and ready", or "Somewhat capable and ready"). Across each sector the response was as follows (n = 208):

Support in place and leadership

Respondents were asked to consider the level of support that staff implementing GIAs receive from people in leadership and management positions. The level of support was reasonably evenly distributed across the 5-point Likert scale (n=187):

- 12 per cent (n=22) said they receive “a great deal of support”

- 19 per cent (n=35) said they receive “a lot of support”

- 21 per cent (n=39) said that they receive “a moderate amount of support”

- 20 per cent (n=37) said that they receive “a little bit of support”

- 6 per cent (n=12) said that they received “no support”.

The remaining 22 per cent (n=42) of respondents provided a written response to the question, “What level of support do staff undertaking GIAs receive from your management/leadership team?”

Of these qualitative responses, 59 per cent (n=13) reported that there was positive leadership support for GIAs, however this was often countered by poor organisational resourcing.

"Support for GIAs is there in principle, but (at least in our first example), management and leadership did not adjust scope or timelines for the project in a way that would have better acknowledged the importance of the GIA and enabled it to be truly embedded in the project planning and implementation."

"Leadership are supportive, but we do not have the resources or staff."

"They're absolutely supportive but do not have capacity to support the roll out of GIAs as there are too many pressing priorities from continuous covid impacts."

"Staff are strongly supported by senior leadership however middle management who are more acutely aware of workloads and pressures are less inclined to support GIAs in the current form and scope required by the Commission. Management and leadership are unable to provide ample practical support for staff undertaking GIAs which is understandable, so this supporting role is being provided via GIA Champions trained up in each unit and GE Officers."

A further 36 per cent (n=8) of respondents reported that their organisational leaders needed greater skills and GIA capability, which many thought could be achieved via leadership training.

"Our management/leadership/executive staff need more training to ensure their competency. Many managerial staff… have not completed any training and do not understand GIA processes and therefore are not equipped to support our staff in the processes."

"As yet management not trained, so unable to provide support and GIAs currently not being conducted within organisation."

"Management and leadership aren't trained in this area, so the only support would be moral/compliance focused, not technical."

Another key theme relating to challenges with leadership support is the understanding that GIA is a compliance requirement, as opposed to an opportunity to create gender equality through culture change that requires ongoing action, resourcing, and continuous improvement.

"The compliance side is understood. Adopting change processes and requiring qualitative and quantitative data captured for reporting across such diverse direct and significant external work is hard to implement. Each area is under-resourced and won't take on additional responsibilities."

"Some management/leadership are involved in applying gender impact assessments. Once the assessment is done, there is a disconnect between making the assessment and applying the recommendations and it then needs to be incorporated into a project or action plan."

"The CEO and Board are supportive of GIA being completed, but it's more about how they practically go about it."

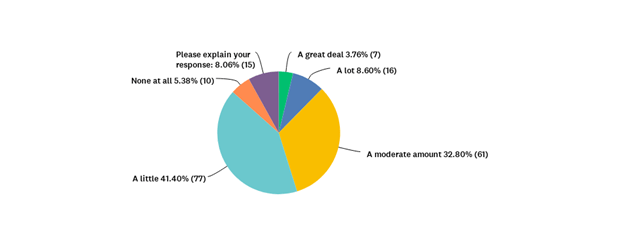

The survey asked practitioners to rate their leaders’ level of knowledge about GIAs using a 5-point Likert scale. Of those who responded, 33 per cent (n=61) of practitioners reported their leadership team had “a moderate amount” of knowledge, while 41 per cent (n=77) reported their leadership team had “a little” knowledge of GIAs.

Additional support to implement GIAs

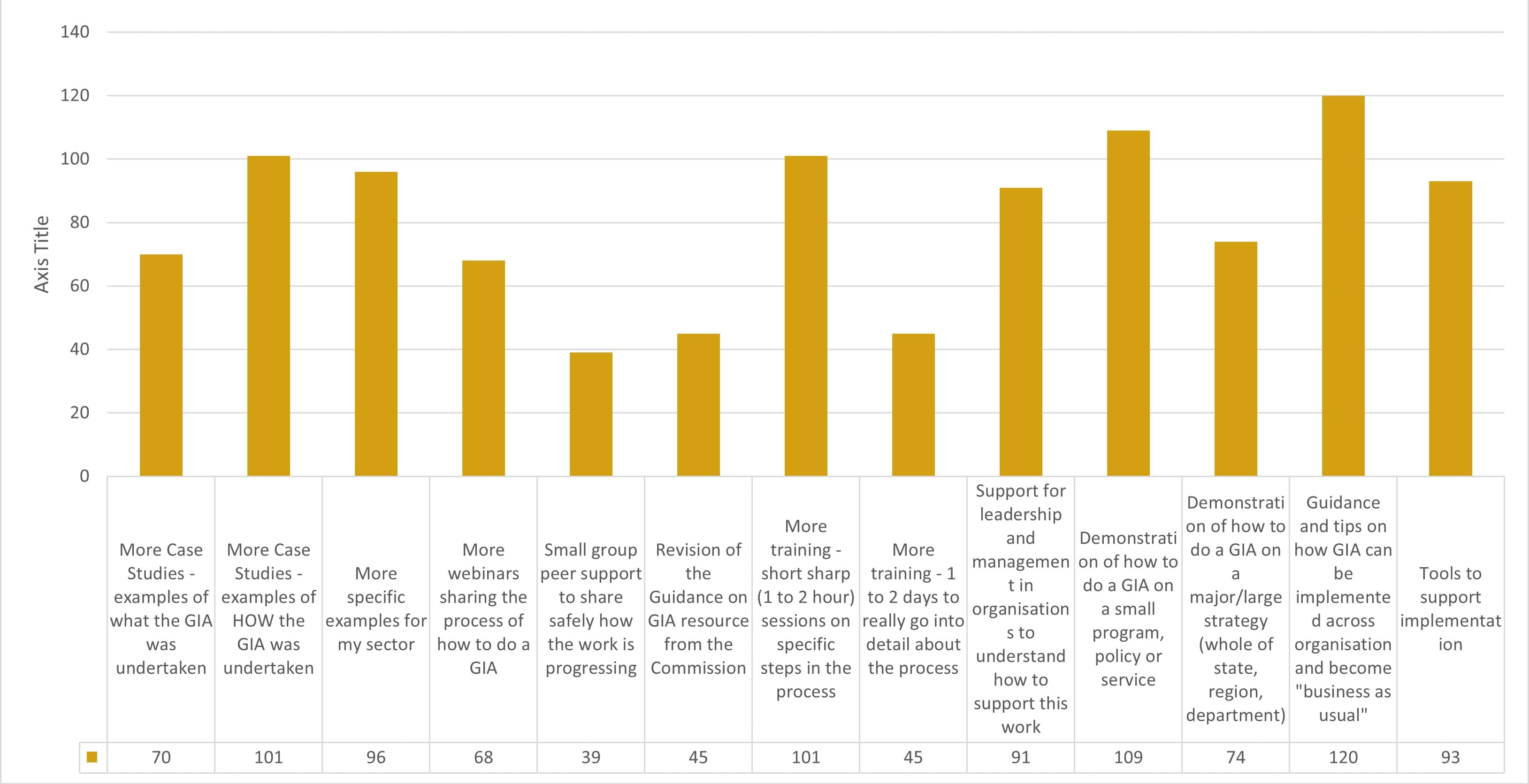

Figure 5 provides an overview of what additional support practitioners want to assist them to undertake GIAs. Respondents were able to choose from a range of options and tick as many options as they deemed relevant. The question aims to understand practitioners’ preferred support options, as well as the volume of interest in the various support options.

Of the 179 responses, the four most popular ‘additional supports’ practitioners would like to implement GIAs were:

- Guidance and tips on how GIAs can be implemented across organisation and become ‘business as usual’ (n=120)

- Demonstration of how to do a GIA on a small program, policy, or service (n=109)

- More training – short, sharp (1- to 2-hour) sessions on specific steps in the process (n=101)

- More case studies – examples of how the GIA is undertaken (n=101).

The qualitative responses to this question highlight the need for clear ‘how to' GIA advice. Practitioners noted that this ‘how to’ advice needs to be in digestible ‘chunks’, use accessible language, and be tailored for specific sectors and settings. Many reported that the Commission’s current GIA guidance is not meeting this need.

"It's guidance on HOW to undertake a GIA and embedding it into BAU that is really needed. This guidance needs to be accessible to the types of people undertaking GIAs (i.e., not GE practitioners)."

"The GIA template needs to be adapted to suit the spectrum of policies, programs, services and strategies/frameworks/plans that require a GIA to be applied. There is little benefit in each organisation trying to adapt the template for these purposes when these would be common experiences sector-wide. The meaningful application of the GIA tool has required more human resourcing… The current guidance regarding what a direct and significant impact still leads to a situation of the vast majority of policies, programs and services falling under the category."

"How to document/report that a GIA has been completed on a policy, program, or service."

"More user-friendly templates with specific questions not open-ended and vague guidance. Contact officers or representatives that can be available for staff to contact to assist with completing a GIA."

"The 4-part template is overwhelming to everyone when they first come across it. So providing examples of a variety of completed GIAs would be useful."

"Short and sharp content that we could provide to teams to support them to complete a GIA would be useful. Also comms content to communicate that this is a BAU initiative and that all teams are responsible for completing GIAs."

"How to apply GIAs across large, state-wide organisations. Information to engage internal departments with limited knowledge (possibly a one-pager) to inform them of the Gender Equality Act and GIA reporting requirements, to assist in inter-departmental resistance."

"Short sharp pre-recorded training for staff who will need to conduct a GIA. We have discovered that most staff will need some training."

"The resources and trainings which have so far been provided to the hospital sector have been too generic and high-level... Any new resources and trainings should be co-designed with the hospital sector to ensure they are fit-for-purpose."

Another qualitative theme that emerged is defined entities’ need to access gender equality expertise – either through the Commission or skilled staff onsite – to support GIA implementation.

"I think the ability to have a consideration from the Commission around the expectations of what organisations can deliver and a support for a deeper capability and coaching support for D&I practitioners, to enable BAU."

"More support is required from the Commission across a number of areas. There is an opportunity for the Commission to get buy in from Boards and Leadership Teams to support the practitioners tasked with delivering in the entities. In many cases this work is being championed and led by individuals at low levels in organisations that are extremely hierarchical… Supporting organisations to understand the why and the anticipated required resourcing is an important contribution that would contribute to positive outcomes."

"Our core expertise is held within 2-3 staff. That is a risk. It would be good if there was training to ensure more people in the organisation are as equally conversant as our current subject matter experts."

"Dedicated training provided on site by a training provider that is tailored for our type of organisation would be ideal - as was done for the Charter of Human Rights and responsibilities when that was rolled out."

"Funding, human resources and outsourced support to complete this work."

Practitioners were asked, “Are there additional barriers or challenges that you or your organisation are experiencing in undertaking GIAs?” Of the 126 responses, practitioners’ answers reinforced the themes of challenges with leadership, resourcing, gender equality expertise, and tailoring and customising educational resources.

The number one barrier reported by practitioners in undertaking GIAs was time, followed by staffing and resources. This was a theme shared by defined entities regardless of their size, sector, and region. The COVID-19 pandemic was noted as an enormous barrier, which was a theme also reported by organisations yet to commence GIA.

"We are a very small health service with no resources to do this."

"Resourcing to ensure the requisite level of competency and knowledge has been developed and embedded into the organisation office holders and our BAU activities as well as adequate compliance and recording processes for both policy and programs have been put in place. We probably have particular barriers due to our size and structure as well as the fact that we service the entire Victorian population… The only way to really progress gender equality and like anything new, will just take time and patience to fully realise the goals."

"As we are a small organisation, resourcing and finding the capacity to undertake the project is difficult."

"Resourcing and time to develop internal processes and educate staff."

"Financial resources - money is tight across the organisation, and the Gender Equality Act implementation/monitoring/ongoing impacts requires a huge amount of input that we do not have the resources for. We do not necessarily have budget to put on more people, or to utilise the panel of providers to assist in this process. The expectations are considerable, and pressure put on organisations to make it work with limited resources is daunting."

"Currently managing workloads with reduced staff due to the impact of Covid."

"Pandemic and workload that results in health… Small rural health services don't have staff appointed to do this work, there is an expectation that this is absorbed into day-to-day workload which is already overwhelming plus Covid."

"Much of what needs to happen is resource intensive or systemic change. Challenging social norms is difficult as is changing the way we do our business. Everyone is so time poor and just trying to get the job done, that anything beyond that is not critical business."

"Lack of staff capacity to undertake the size of implementing the GIA process. Funding for additional staff and hours would be beneficial to progress the requirement."

"Time and resource constraints - linked to covid, rate-capping and lack of understanding from leadership of the need to apply a GIA early but also allow the time for a GIA to be undertaken - and that this can be an iterative process for big projects - which will have an impact in terms of timelines (but a much better and more robust outcome in the end)."

Questions for defined entities who have not commenced GIA

The survey asked specific questions of practitioners from defined entities who are yet to commence GIA work. This part of the report details their survey responses.

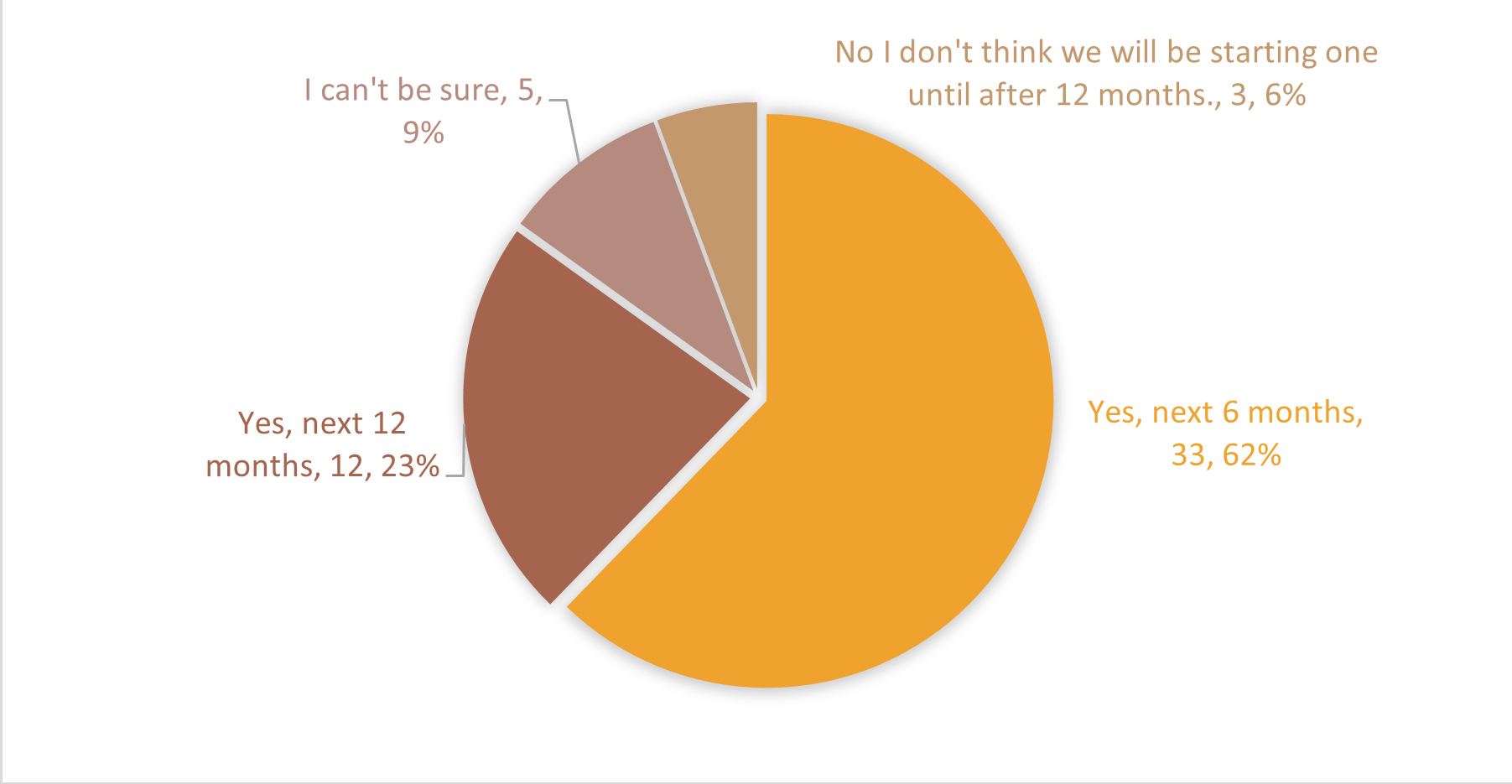

Of those respondents that had not started GIA (n=53), 62 per cent (n=33) stated that their organisation intended to start a GIA in the next 6 months.

Practitioners were asked, “Why have you not commenced a GIA yet?” The majority of respondents, at 28 per cent (n=15), reported that their organisation had not commenced GIA due to a focus on completing the GEAP. The decision regarding organisational priorities was also driven by limited resources and time (n=9) and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (n=4). This was a barrier also raised by organisations completing GIAs.

"Focussed on WGA and GEAP."

"We have been focusing on the data audit and now completing the GEAP before commencing."

"Limited EFT for delivery of the project. Currently working on GEAP."

"Because of the time and effort it has taken to complete the audit and upcoming GEAP submission. We do not have a dedicated team for this and it has to be absorbed into BAU roles which has been incredibly challenging."

"Main focus is on completing GEAP for the upcoming deadline and providing training and resources to employees and organisational champions to prepare them to carry out a GIA. We are also not at the stage where we have not yet prioritised which policies programs and services should have a GIA."

"Small organisation with limited resources/capacity to absorb an additional requirement in an operating environment heavily impacted by COVID. Focus on GEAP then GIA training to commence."

"All available resources have been directed to meeting our obligations relating to the development of our GEAP. We intend to commence a GIA once these activities have been completed."

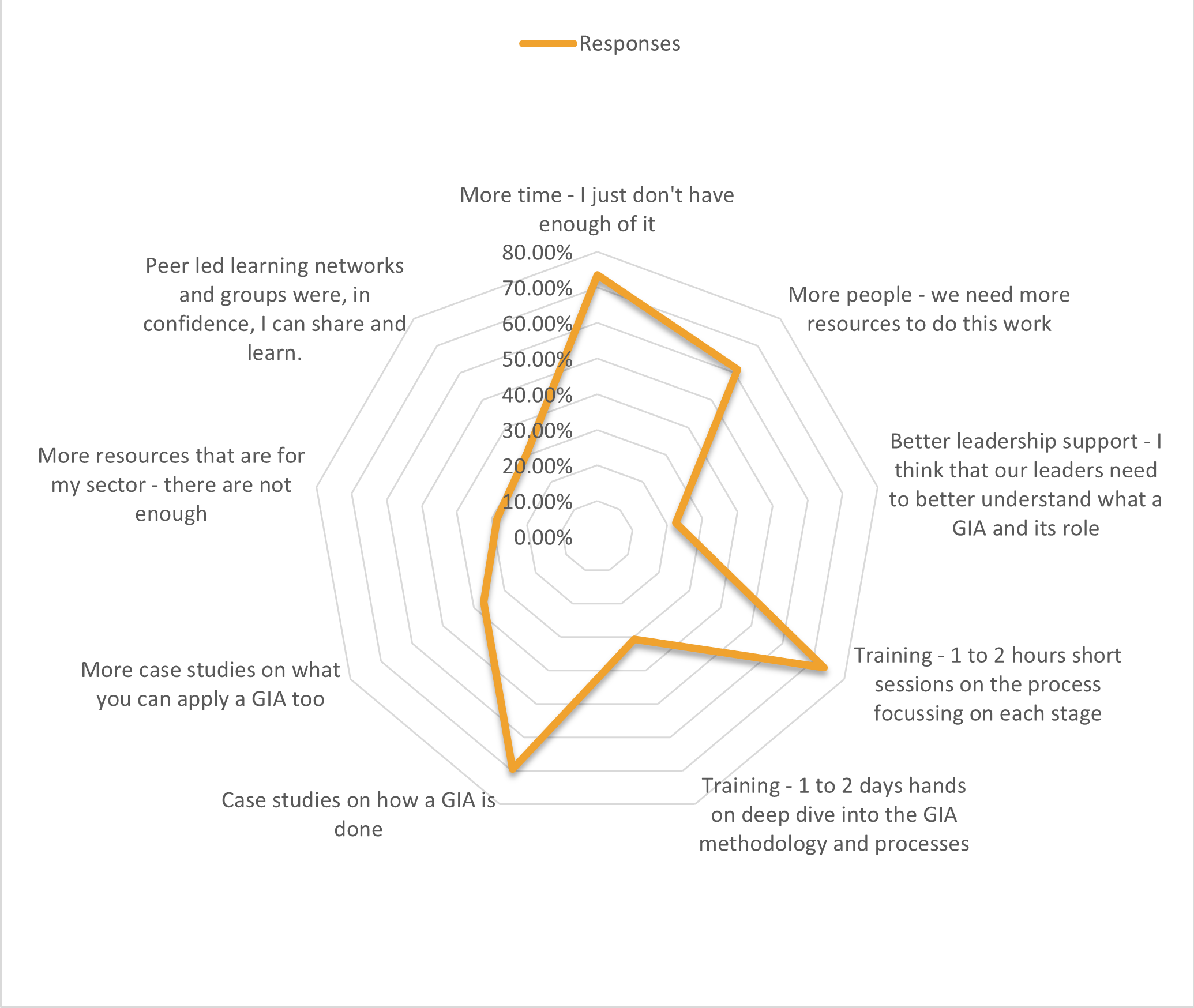

Practitioners were asked, “What support do you need to commence a GIA in your organisation?” The top three support needs identified by practitioners whose organisations were yet to commence GIAs were:

- 73 per cent reported “more time – I just don’t have enough of it”

- 73 per cent reported “training – 1 to 2 hours short sessions on the process focussing on each stage”

- 69 per cent reported “case studies on how a GIA is done”.

Fifteen practitioners provided a qualitative response to the question regarding what support their organisations needed to commence GIA work. Similar to organisations who are completing GIAs, organisations yet to commence reported that they need access to gender equality experts who can provide guidance on GIA implementation (n=5).

"A gender equality expert that can guide and lead GIAs when triggered is sorely missing."

"Not sure we need to do one. Would be good to be able to talk someone about that. We are to merge with three other defined entities within the year, which may mean we would have to review and change anything done."

"Someone that can answer basic questions that pop up during the course of a GIA."

Sustainable training was also noted as an important educational support and capacity need (n=5) to increase understandings of how to implement GIAs.

Focus group and interview results

The interviews and focus groups sought to understand the barriers and enablers that defined entities experience when implementing GIAs by exploring the questions detailed on page 10 of this report.

Time and funding

The COVID-19 pandemic – Key external threat to GIA implementation

Across interviews and focus groups, one of the most significant barriers to implementing GIAs is the significant time and resources required to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is acutely experienced by the health sector and other frontline services such as local government who identified that their GIA implementation had been hampered by the Victorian COVID-19 public health directions, furloughing of staff, and other public health policies such as the ‘code brown’.

"I just think asking staff to do anything at the moment in the current environment is very, very difficult. There's so much pressure on so many staff with the code Brown and, you know, COVID, furloughs and whatever." (Health Focus Group)

"I spent a lot of time explaining why gender equality was important and what a gender impact assessment was. And then the staff was so busy, and so under the pump, with or without COVID, that just finding a time to meet was impossible." (Health Focus Group)

"I don't think other public entities have had the same burden that councils have through COVID. Whether it's working out how MCH [Maternal and Child Health] and Disability Services and libraries and everything's going to operate has been enormous and it's really, really, really hard for officers. And that’s what we’re talking about here is officers trying to get this, like front and centre of a leadership team… dealing every day with every change… impacts on councils and their public health… it's just huge." (Local Government Focus Group)

Financial resources and time

Interview and focus group participants spoke of scarce resourcing – both financial and staff time – which impacts their ability to thoroughly conduct GIAs. Some organisations reported having an operational budget to embed GIA work, which appears to be related to the maturity of the organisation and their existing structures to undertake diversity, inclusion, and gender equity work.

Practitioners who attended the Rural Victoria, Sports and Recreation Focus Group noted that their biggest barrier to GIA is scarce resources. Many entities’ resources are scarce due to the COVID-19 pandemic response and therefore dedicating time, staff, or financial resources to GIAs is not possible.

Smaller organisations in rural and regional Victoria reported a lack of financial and staffing resources significantly impacted their capacity to undertake GIAs.

Interview and focus group participants report that the availability of resources is a critical enabler for the GIA process and ensuring buy-in across the organisation for its outcomes and goals.

Capacity and capability

Interview and focus group participants reported that while there are organisations that have built capacity to understand GIAs, many organisations are yet to do so.

The Local Government interviewee highlighted that some local councils have sufficient internal capacity to conduct GIAs due to gender specialisation already embedded in their organisation. However, this expertise is not consistent across the sector and there is no oversight for varying capacity levels and limited support for councils yet to build this knowledge. This interviewee noted further work is required to build capability among councils, including introductory gender equality training. This position was supported by participants who attended the Local Government Focus Group.

Similarly, participants who attended the Educational Institutions Focus Group highlighted that while there was great support for the GE Act and GIAs, a lack of resources has meant that GIAs have had minimal impact in their sector. One participant in this Focus Group noted the impact as “less than inspiring”.

Many noted that a lack of resources – that includes gender equality expertise – has resulted in GIAs becoming a compliance exercise.

"There are huge competing priorities (against doing GIAs). We don’t want tick and flick but it could end up getting that way." (Educational Institutions Focus Group)

"So we started off really well with a working group with leadership on board with training and programs, and then do due to changes of staff and portfolios, I'm kind of now trying to pick it up... We had a diversity person for... three or four months it was sensational. And she then for her own reasons, has left…[I’m in] panic mode, I've got all these competing priorities. I don't want this to be a tick and flick. It's really important to me, but I believe we're running the risk of potentially getting it that way." (Educational Institutions Focus Group)

Participants reported that resources are a critical enabler to the success of GIA. This includes resourcing all stages of GIAs, including communication and support, adapting and applying the process to different areas and departments of a defined entity, training, and leadership and staff development.

Value of building capacity before GIA implementation

Interview and focus group participants reported that investment in training on GIAs and gender equality prior to implementation is a critical enabler for success.

"People do see the value after doing the training." (Educational Institutions Focus Group)

"Not until the … training on GIA that people suddenly go “I get it.”" (Educational Institutions Focus Group)

Some organisations reported that they had invested in building the capacity and capability of their staff prior to GIA implementation.

Interview and focus group participants from defined entities who did not undertake training prior to commencing GIAs found it was more difficult to get traction.

"I did get some people on board, but not everybody could really follow what I was saying. And the time and the headspace to put towards it was just too big… it was just really hard for people to get their head around." (Health Focus Group)

"Without somebody to have a portfolio that actually has gender equity and prevention of violence against women and whatever in their job description, well, you can't expect them to be able to somehow just create... I mean, who's gonna actually be the champion of this work across the organisation?" (Local Government Stakeholder Interview)

Some organisations reported that they were able to bring in external expertise, but only as a support resource, rather than an ongoing resource that could build internal organisational capacity.

Access to gender equality expertise

Interview and focus group participants reported that access to gender equality expertise in the form of personnel, external consultants, and skilled workers is an ongoing issue for their organisations’ GIA implementation.

For some larger public sector entities, the issue of gender equality expertise is linked to the scale of GIAs being undertaken. The State Government Agency interviewee reported challenges associated with scaling up a GIA to apply it to an extensive 10-year Government strategy. They couldn’t source best-practice examples for projects of this scale and struggled to determine how broadly to scope the work and what their final outputs should be. They would like to see resources of this kind provided.

The value of partnering with gender equity experts

Many interviews and focus group participants reported that an enabler for the success of GIA is the ability to access gender equity expertise. This was noted as critical to enabling staff in-house to partner with subject matter experts and their colleagues to apply the GIA process.

Participants from the Regional Local Government Focus Group – which is comprised of a range of sectors – reported that many entities have limited gender specialisation within their current workforce. This focus group reported that while there is generally limited access to gender specialisation within their organisation, partnering with organisations like Women’s Health Services provides valuable resourcing to support GIAs. Participants reported that sharing knowledge through collaboration and networks is an enabler to build gender equality expertise and capability.

It was noted that especially within larger entities, building organisation-wide gender knowledge is challenging. Employing specialist staff to lead the work can mean that this knowledge is not embedded. Similar issues with access to expertise were also highlighted for smaller organisations with limited resources to employ external consultants.

Many defined entities spoke of the need to build sustainable gender equality capacity within their organisations. The State Government Agency interviewee noted that arranging consultants to conduct GIA work was not sustainable, and there is a need to build capacity within the Victorian Public Service (VPS). This interviewee also noted that their GIA was time-consuming and that time constraints are likely to be a significant barrier in the future. They recommend the VPS provide ‘internal consultants’ with gender specialisation to assist with GIA work.

The role of the Commission

Interview and focus group participants spoke of the Commission’s expertise and leadership as a critical enabler to GIA success and cultural change to promote gender equality in Victoria.

"We were really blessed and we had a strong connection with the Commissioner. And that was something that we initiated right at the start across that pilot program." (Rural Victoria, Sports and Recreation Focus Group)

"The Commission could actually really support practitioners by them having those conversations with leaders, and then leaders coming to the D&I practitioner or others, and saying, ‘Hey, this is really important for our organisation.’ There's a great opportunity for us to make a contribution to creating gender equality across our community." (Water Utility Interview)

Participants acknowledged that the Commission has a large reform agenda. Many reported a need for the Commission to provide greater GIA resources, support, and to be more accessible to the sector.

"The Commission has done a power of work to try and really translate, you know, the government's just handed in this agenda, which I'm completely supportive of… You know, they've now got to implement that… Dr. Vincent has done a power of speaking… But yeah there's a whole lot more that we need." (Educational Institutes Focus Group)

"I understand that they've [the Commission] probably been smashed just like us. But it's just made it, like, so much more pressure on us, because they haven't had this response. And leading up to the gender audit, they did get a whole lot quicker… I got responses within a day." (Health Focus Group)

"You go to the Commission [website] it's big. It can become quite overwhelming the amount of resources to get your head around and everything else." (Regional Local Government Focus Group)

The Commission staff who participated in a focus group were highly cognisant of the opportunities provided by the GE Act in creating meaningful social change, as well as the limitations associated with a time of immense change and disruption within the public sector.

The Commission staff discussed the range of education and support required by the Victorian public sector to effectively implement GIAs and the requirements of the GE Act.

The Commission staff also noted tension regarding sector expectations and the volume of organisations, and the Commission’s finite resources to implement the broad remit of the GE Act. This includes promoting and advancing the objects of this Act, supporting defined entities to comply with this Act, and providing advice to defined entities about the operation of the GE Act, among other obligations. The Commission’s role as a regulator and the tension and opportunities regarding supporting defined entities to improve gender equality and ensure they comply with the GE Act was also discussed.

Access to simple, targeted resources tailored and contextualised to sectors

Interview and focus group participants consistently noted that the Commission’s current GIA tools and resources are too complex and need to be simplified and contextualised for different sectors. Many entities reported barriers to sourcing their own training due to expense and that the Commission’s training resources had limited relevance to their work. Large defined entities also reported challenges in scaling up the advice for large projects and initiatives.

"The length of the Commission's toolkit was a barrier for some of our departments." (Local Government Focus Group)

"I kept feeling like every time I'd return to the guidelines from the Commission, it was just pushing me into feeling like I was doing my thesis again... really hard work." (Health Focus Group)

Participants reported that accessible, simplified resources that support defined entities to understand the basics are needed, as well as resources that engage diverse learning methods, such as video content.

A consistent barrier identified throughout the interviews and focus groups was that the current Commission guidance is not tailored and customised to different defined entity sectors.

Many defined entities, as well as the Commission, reported that tailoring and customising guidance for different sectors and their GIA work would be of great benefit.

Sector and regional-based practice forums and communities of practice

A number of focus group and interview participants identified the need for greater collaboration and knowledge sharing across sectors. It was noted, for example, that different councils are concurrently working on similar GIA projects, and it would be efficient for learnings to be shared in real time.

Many noted that a lack of resourcing meant that no-one has capacity to facilitate sector-based or regionally based practice learning forums or communities of practice. Many defined entities reported a strong willingness to share what they have learnt and contribute to collaborative models to build sector capacity. For example, the State Government Agency interviewee reported considerable learning during their GIA process and were interested in exploring ways to increase collaboration between government departments and defined entities to share learnings and promising GIA practice. One practitioner noted:

Leadership capacity and organisational structures

Interview and focus group participants spoke of the critical role and capability of leaders to create an authorising environment for GIAs to occur and their recommendations to be implemented. The leadership environment is crucial to GIA work, with some focus group and interview participants describing how leadership set up an ‘authorising environment’ that allowed staff coordinating the GIA to be ‘backed’. There were examples of leadership involved in the process to set up and implement GIAs, which had positive benefits.

Some interview and focus group participants made the observation that it can be challenging to determine who is accountable for GIA work within their pre-existing organisational structures, which can lead to GIAs not being effectively implemented. Embedding the GIA process within existing organisational structures and practice was also noted as a barrier. Many noted that senior leadership engagement is critical, as leaders must support and drive GIA engagement.

"There's internal discussion almost around, where does it sit? And I think that sort of supports what a few areas are finding as far as who's responsible?" (Regional Local Government Focus Group)

"I think the way that the Act is set up, and the guidance is really, really, really good practice, but I think our systems don't allow us to do the best practice. Our systems and the way we are organised is… quite siloed." (Regional Local Government Focus Group)

The Commission reported that having a good organisational structure and the positioning of GIA work does impact its application. The Commission also noted that the practice of retrofitting GIA to policies, programs, and services is occurring, as well as concerns regarding the ongoing tension of working with leaders within the system, while also seeking to lead change regarding entrenched attitudes and behaviours, structures, and systems of inequality.

Practitioners noted examples of organisations setting up appropriate structures and processes prior to GIA activity, which appear to be producing positive results.

Whole-of-organisation ownership vs the work of ‘human resources’

A reality for many practitioners is the persistent practice of locating GIA work within a functional department. The challenges with this approach were highlighted by the benefits reported by organisations that took a systemic view of GIAs. This approach seeks to locate GIAs within an authorising environment and as a systemic and strategic organisational practice.

Several defined entities had situated GIA in their human resources departments who had led the GEAPs, based on the assumption that these were similar pieces of work.

The Commission is conscious of the role that specific teams play in driving the implementation of GIAs and how they need to be positioned within the broader organisational structure to achieve whole-of-entity GIA practice. They note that a key issue in driving practice across entities is attrition of key staff and their skills.

Opportunity for coordinated GIA implementation across sectors

A few members of focus groups and interviews pointed to the opportunity of coordinating priority areas of GIA across sectors. Some sectors had come together to customise, tailor, and apply the Commission’s GIA guidance material by using a specific group or network of like organisations:

"There are some sort of generic systems that sit across hospitals that people are familiar with, and it's a language that people use about how you get policies and procedures to work in a hospital setting." (Health Focus Group)

Its opportunities for the [Education]sector to align on a whole-of-sector GIA on policies, programs and services that are common across all of our organisations. So I don't know how much of this work has been talked about with the [State Department level] Coordinator … but we are working a lot more in alignment now and expected to." (Educational Institutions Focus Group).

GIA implementation across sectors was also seen as valuable to encouraging consistent practice and approaches. Practitioners suggested that GIA implementation would benefit from high-level communication sent from key public sector leadership, including Ministers, to support GIAs and articulate the benefits to defined entities.

The State Government Agency interviewee noted that coordination and collaboration also reduces the likelihood of duplication. This interviewee identified the possibility of multiple government departments analysing the same data sets to extract information for GIAs on different projects and exploring opportunities for sharing insights across departments and teams.

Push back, culture, and fear associated with gender work

In some interviews and focus groups, there was discussion regarding the theme of resistance and backlash to GIA implementation, with entrenched cultures causing real challenges for some practitioners.

Some practitioners spoke of more subtle forms of resistance, which resulted in major opportunities to undertake GIAs being missed:

The Commission also noted resistance to the GIA process coming through in the form of fear and concern of ‘getting things wrong’. This view was reinforced by an interviewee who reflected the risk that leaders and organisations can feel when doing gender equality work and the role that the Commission can play in alleviating fears within the sector.

Analysis

Across the survey, interviews, and focus groups, defined entities are broadly seeking greater:

- Support, funding, and time

- Tailored and accessible sector advice, guidance, and templates

- Targeted training, capacity building and practice-based learning opportunities

- Access to sustainable gender equality skills, knowledge, and expertise.

Another overarching theme was the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been a major detractor and inhibitor to the implementation of GIAs and the GE Act for public sector services. Nowhere is this more evident than in the health sector, which reported that public health directions and protocols reduced resources for implementation, deferred the work completely, or diluted funding to such an extent that it was incredibly difficult to achieve deliverables.

Leadership capability plays a critical role in driving the work to undertake and implement GIAs, particularly in terms of understanding:

- the transformational nature of GIAs and the GE Act’s intent

- the practical work required to undertake a GIA.

Many participants and respondents reported strong support from senior leadership and executives. However, for many organisations this does not translate to applied practice across the organisation and to frontline teams who are doing the work.

A lack of funding and resources was a critical theme throughout the consultations. This included a skills shortage in the gender equality workforce, the diverting of funds for other priorities, and, in some instances, a lack of value placed on gender equality work.

Defined entities’ different support and educational needs

An analysis of the survey, interview, and focus group findings clearly shows that there is a distinct set of characteristics associated with defined entities that are successfully implementing GIA work, compared with those that are struggling or who are yet to commence implementation. The characteristics strongly inform the type of educational support that defined entities seek to implement GIAs.

Defined entities that are successfully delivering GIAs are characterised as having:

- Organisation-wide training on gender equality that articulates the value proposition for the organisation, its workforce, and individuals.

- CEO leadership with the executive team driving implementation and sponsoring GIA work.

- Translated the Commission’s GIA guidance to their industry context and organisational approach.

- Organisational policies, procedures, and structures that support and embed the development, implementation, and action of GIA recommendations.

- Gender equality expertise that is in-house and that can be drawn on externally. This includes GIA leads and officers who understand emerging policy, program, and service planning, and its effective integration with the organisation’s strategy.

- Alignment of GIA work with other legislative, regulatory, and strategic drivers and frameworks.

- Minimal environmental pressures and strategic risk factors that impact the entity.

Defined entities that are successfully delivering GIAs request educational support that is strategic and that further builds their internal skills and capability. These entities are requesting advice and case studies on how to advance systems, structures, and leadership that promotes GIA and aligns with the external legislative environment. This consultation reveals there were few entities that are displaying these characteristics.

Defined entities that are struggling to implement GIA are characterised as having:

- GIA work centralised and often located in their human resource team.

- Minimal executive leadership support, including leaders who are absent, low levels of buy-in and advocacy for GIA.

- No access to gender equality expertise internally or externally that includes low gender equality capability, knowledge, and skills among staff and leaders.

- The use of generic resources and guidance that are not contextualised to the sector or organisational context.

- Minimal or no staff training or development.

- Officers and project leads who are isolated from whole-of-business knowledge and therefore unaware of emerging GIA opportunities.

- Lack of alignment to other legislative and strategic frameworks.

- Significant environmental pressures and strategic risk factors (i.e. the COVID-19 pandemic, state and local government elections, large organisational restructures).

- Structural barriers including poor organisational structures that support GIA, lack of management and leadership consideration for how GIAs will occur across organisational models.

- Geographic location as an additional barrier for rural and remote organisations.

Defined entities that are struggling or yet to commence their GIA journey request educational support in the form of training, resources that provide prescriptive step-by-step procedures on how to undertake a GIA, as well as funding to resource the work. The consultation findings suggest that these entities are the majority.

Foundations of recommendations

There is a set of underpinning factors and relationships that identify characteristics of defined entities that are succeeding and struggling with GIA implementation. These factors need to be considered as central in the design of the GIA education strategy for the public sector.

The three interconnected aspects are defined as:

Continuum of readiness for a GIA and transformational change

A defined entity’s readiness for transformational change can be seen on a continuum of behaviours in relation to GIA. Consultation feedback demonstrates that greater organisational readiness broadly translates to greater alignment with the objectives of the Act.

- GIA is a prescriptive process for compliance vs GIA is a guiding process to help enable cultural change and continuous improvement

At one end, the prescriptive approach employed by defined entities (as reported by participants) is often described as a ‘tick and flick’ activity to ensure compliance with the GE Act. GIAs are undertaken to mitigate risk of non-compliance with the legislation. This approach is not transformative. At the other end of the continuum, defined entities are deliberate in applying GIA as a mechanism to create social and community change. In this approach, GIAs are deliberately undertaken to identify and redress intersectional gender inequality within the organisation that has led to the design of inequitable policies, programs, and services.

- Implementation is driven by frontline project leads vs GIA is owned across the organisation

At one end of the continuum are practices whereby the GIA implementation is seen as the responsibility of an individual frontline practitioner. The approach often sees GIAs driven by a frontline officer who does not have the delegation or role jurisdiction to mandate significant procedural change for organisation-wide GIA activity. Nor does this worker have the authority to implement or influence the outcomes of GIAs within and across the organisation. At the other end, the GIA process is embedded through systemic and structural organisational procedures and policies and there is a distributed ownership of GIA implementation.

- The defined entity is fearful of gender equity work vs there is a positive view of gender equality reform

At the ‘transformational gender equality’ end of the continuum, GIAs are implemented in a context whereby intersectional gender equality is viewed by leadership and the organisation as an enabler to becoming a better provider of public services and to ensure that the organisation aligns it resources with public need. At the other end of the continuum, organisations have no or limited language around gender or intersectionality. There is a concern about gender equality work that is driven by a lack of understanding about its benefits. Gender equality work is seen as a specialised skill set that is limited in its distribution across the organisation. In extreme cases, gender equality is seen as punitive and about controlling behaviour, rather than enabling and empowering.

- GIA implementation is centralised with coordination of the implementation held in a unit vs GIA implementation is distributed through to localised units and teams that are accountable for their own outcomes.

At one end of the continuum GIA work is centralised within a department, which is often human resources or a centralised policy unit. The centralised approach can impact the ability for GIAs to access the range of skills required for an effective assessment. This includes service design knowledge, client and customer feedback and usage data, resource requirements, and gender equality skills and knowledge. At the other end of the continuum, GIAs are delegated to different units and divisions that are held accountable by central leadership for the process and its outcomes. This approach enables closer access to the knowledge and impact of the service under review, builds capability at the local unit level and promotes organisational transformation.

- GIA advice is sought through the Commission vs there are localised gender equity skills

Access to gender equality skills and knowledge is required to deliver transformational gender equity outcomes. At one end of the continuum, investment is made by the organisation to develop and acquire gender equality skills, knowledge, and practice to shift the entities systems and procedures. At the other end of the continuum, defined entities look to the Commission to provide access to gender equality skills, knowledge, and resourcing, as a publicly funded entity who is seen as an ‘information line’ and resource for the public sector.

Across all the interviews and focus groups, different combinations of these continuums were observed. Some entities sought advice from the Commission on gender equality but also had a strong enabling view of gender equity, while delegating the work of GIAs to frontline staff. Those entities that did have ‘successful conditions’ for GIAs often had invested in the development of in-house gender equality skills, had a balanced distribution of GIA delegation, and whole-of-organisation ownership of the process and outcomes. By contrast, entities that were struggling tended to sit on the other end of the continuum.

The value placed on gender equality skills, knowledge, and activity

Defined entities’ position on the continuums as defined above also has implications for the value that they place on gender equality skills and knowledge, and how willing they are to fund and resource GIAs. Organisations that displayed characteristics associated with the transformational outcomes of the GE Act are more likely to invest in gender equality skills and expertise. These organisations acknowledge that to achieve the outcomes and benefits of intersectional gender equality, this work needs to be funded via whole-of-organisation training, in-house gender equality expertise, and consultants as they build internal expertise.

Organisations at the other end of the continuum – where GIAs are prescriptive, compliance-driven activities and equality work is not defined as an organisational enabler – are less likely to invest in the resources and skills required to achieve the outcomes of the GE Act.

Gendered nature of gender equality work

Throughout the interviews and focus groups, another observation about the value placed on gender equality skills and activity was evident. Consultation participants were overwhelmingly women, in short-term contracts or part-time roles, did not have the authority to manage resources and were most commonly doing gender equality work in addition to their current job.

Indeed, the workforce that drives the implementation of the Act is subject to the same drivers of inequality that they are trying to redress – poor reward and recognition, low resourcing, and assumptions that this work does not require specialised skills or funding.

This project was not designed to undertake a workforce gender analysis of gender equality workers and employees in public entities. However, if the Commission is to realise the intent of the GE Act, the gender segregation and composition of this workforce, which reinforces inequality, must be addressed.

Role of the regulator – The Commission and the Commissioner

The Commission’s role was regularly raised throughout the consultation by those we interviewed. Linked to the need for access to expertise and support, participants regularly talked about wanting access to the Commission for gender equality knowledge, skills, and guidance. Defined entities view the Commissioner and the Commission as a highly credible source of information and advice.

This report does not seek to provide advice and direction to the Commission on what its role is or should be, only to highlight the feedback on the Commission’s work and resourcing and what opportunities there may be going forward.

Defined entities are seeking greater access to the Commission. The access that is being sought depends upon where the entity is on the continuum of readiness, and the value that they place on gender equality skills and expertise. The support needs that are being sought from the Commission are either:

- more prescriptive advice and stepped-out resources for the entity’s sector, size and scale, and geographic location; or

- feedback and strategic advice on gender equality and its application to the entity’s specific context and goals.

The Commissioner was established as a regulator of the GE Act and has legislative powers to enable and require compliance with the Act.

This report highlights that in the first instance, a number of the key functions of the Commissioner are about developing the public sector’s capacity and capability when it comes to gender equality, and the GE Act uses such words as promote, support, provide advice, undertake information and education programs, encourage best practice, and facilitate compliance.

The capacity and capability of the Commissioner, and the resources available to her to fulfil her statutory functions and duties, will inform the type of support and resources that are available to achieve the outcomes of the GE Act.

The role that the Commission can play should be communicated more throughout the public sector and mindful of the range of expectations that is in play. We do not suggest that the Commission can play all the roles expected of it. However, it may be that by understanding these requirements, pathways to achieving them can be outlined.

A clear position on the type of regulator the Commission is will provide a stronger foundation for the resourcing and support that the Commission wants to provide, the system and strategy to deliver that support and resourcing, and an opportunity to engage with key stakeholders on how this should be funded and resourced.

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusions

The survey, interview, and focus group analysis provides contextual markers and realities surrounding the implementation of GIA. The consultation found that the major barriers and challenges to the consistent implementation of GIAs across defined entities are:

- Lack of resources, funding, and staff time.

- Lack of access to internal and external gender equality expertise, which is linked to how defined entities value this skill set and whether they are willing to resource it.

- Lack of access to tailored, contextualised, highly practical templates, tools, and training that detail how to implement GIAs.

- Need for improved leadership models and capacity to support the implementation of GIA work throughout defined entities to realise transformational change and the objectives of the Act.

- Insufficient clarity on the role of the Commissioner and Commission in supporting defined entities to implement GIAs.

Recommendations

Invest in resources that are tailored and customised to specific sectors and regions

Develop highly tailored and customised sector resources to support the effective implementation of GIA. This includes access to resourcing – including funding and staff time – and the expertise required to support the Act and GIAs to build sustainable skills within the public sector to embed the work and fully realise intersectional gender equality.

It is clear to the authors of this report that there are immediate needs that can be implemented. Overwhelmingly, there is a need for defined entities and their workers to understand how to undertake GIAs. The following are suggestions only, and developed on the understanding that there is limited access to gender lens expertise in organisations:

- Small, bite-sized training, in small, sector-specific groups, on different stages of the GIA process – e.g. 'Understand your context (data and the GIA)' for Local Council Metro, 'Defining issues and challenging assumptions' for Primary Health Care Services, 'Options Analysis' for Rural Hospitals. Delivery could be via case study methodology to allow for in-depth practical investigation for a specific sector.

- Short, sharp videos that step through specific components of GIAs simply and clearly. These can include interviews and examples from current practice and be tailored to specific ‘resourcing’ types of defined entities. For instance, the Commission could produce a 5-minute video on Options Analysis, which steps through this component of a GIA, and demonstrates how this stage occurs by interviewing a large, well-resourced defined entity that is city-based, a smaller rural organisation with limited resources, a defined entity with more centralised decision making, and another defined entity with decentralised processes.

- A master class on integrating GIA practice into ongoing business practice. Again, using case study methodology and providing a tailored experience to the sector, this master class can seek to build capacity across the defined entities to act as subject matter experts for this area.

- Deliberate practice sessions can be run at a regional/local level on specific, in-progress GIA work. In smaller groups where existing trusting relationships exist, defined entities can be invited to bring their GIA work to a practice session where GIA work can be discussed in detail. This could draw upon the well-known community of practice approach, but more targeted to existing relationships that are trusted enough for honest conversation about what work is being undertaken and how it can be strengthened. Through this, resources and peer-led practice can be shared.

- Targeted, sector-specific round-table conversations with executives in defined entities around leadership of GIA, including examples of process, policy, and (drawing upon the current project) evidence of what is best practice and required to achieve outcomes for the GE Act through GIAs. These sessions could be framed through an ‘organisational change’ perspective and in partnership with the VPSC.

Create resources that are about the ‘how’ of the GIA process

Create new products and tools that describe the specific process of how to undertake a GIA, including tangible practice examples of how workers and organisations can implement GIAs. These tools must be accessible, support practitioners to understand the basics, and engage diverse learning methods to encourage learning and build practice expertise. Resources that practitioners requested include:

- Guidance and tips on how GIAs can be implemented across organisations and become ‘business as usual’.

- Demonstration of how to do a GIA on a small program, policy, or service.

- Case studies that provide an example of how GIAs are undertaken.

- Short, sharp training modules as detailed below.

It is recommended that the Commission review its current GIA guidance and resources to ensure they are accessible to practitioners who are not gender equality experts.

Fund, design and deliver targeted training sessions on specific aspects of the GIA process

Design and deliver short, sector-specific training sessions that provide modules on specific aspects of the GIA process and implementation. This includes applied practice examples of how defined entities can assess whether a policy, program, or service has a direct and significant impact on the community. These training modules need to balance theory and applied practice, and showcase practical, accessible examples of how practitioners can implement GIAs.

Support leadership capability development – from executive through middle management

Provide support to build leadership capacity and capability to embed and strengthen understandings of gender equity and what organisations need to do to deliver on the objectives of the GE Act. This strategy must target CEOs and executives, right through to frontline middle managers and supervisors.

It is recommended that the Commission facilitate and enable the leadership of defined entities to:

- Understand the role of leaders in transformational change as it relates to intersectional gender equality.

- Build ‘know-how’ on the process and purpose of GIA as a key strategy and protocol to create gender equitable outcomes for Victorian communities.

This could take the form of:

- Coaching and mentoring

- Communities of practice

- Targeted training for executive leaders and managers on transformational leadership to advance gender equality

- Advice for defined entities on the leadership skills and capabilities that need to be developed to support transformational gender equality change. This could be used by defined entities’ learning and development teams to inform annual training schedules and plans.

Support, encourage, and enable collaborative practice and sharing