Driving gender equality through the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic)

Under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act), organisations covered by the Act – known as defined entities – are subject to a number of obligations that require them to take positive and transparent action towards achieving gender equality in their workplaces and in their public policies, programs and services.

The elements of the Act that embed this transparency and progress towards gender equality are part of what makes this legislation nation-leading.1 While comparable legislative frameworks nationally or around the globe may require the submission of gender equality data, most do not require organisations to publish their data, develop action plans to address any inequalities revealed in the data, or make reasonable and material progress to promote gender equality in every 2-year period.2

The Commission is committed to supporting defined entities to meet their obligations under the Act through improved training, education, and guidance resources. This baseline report of workplace gender audit data and the Commission’s upcoming in-depth analysis of each organisation’s Gender Equality Action Plan (GEAP) and companion baseline report on intersectional analyses, will help the Commission understand how to tailor its support in future years. It will also help defined entities understand what actions they need to take to embed systems and processes that support full and effective compliance with the Act.

The Commission acknowledges the effort and dedication of the people in defined entities across the state who have undertaken this important work, many for the first time. We recognise the powerful contribution this will make towards achieving gender equality in defined entities and the broader Victorian community.

Establishing the baseline for ongoing progress

This Baseline Report covers the key findings from the inaugural workplace gender audit data collected under the Act in 2021.

Establishing how defined entities are tracking towards workplace gender equality is crucial to ensuring we can build on the gains we have already made in the public sector. Synthesising these results is also vital to support the sector to address persistent blockers of, and accelerate progress towards, gender equality.

It is important to recognise that this is the first time that defined entities have been required to conduct a workplace gender audit. As such, the audit has revealed areas of limited data availability and poor data quality (particularly in relation to intersectional data).3 Where existing processes did not allow for the collection of sufficient data, or did not yet exist, organisations were asked to specify how they would rectify this as part of their GEAPs. Similarly, the Commission will work to improve its systems and support entities to improve their systems, in order to improve data quality over time. A process evaluation will be undertaken to identify areas for improvement and ensure greater efficiency and quality in future reporting rounds. Specific recommendations for actions to improve data quality are included throughout this report.

The gender pay gap

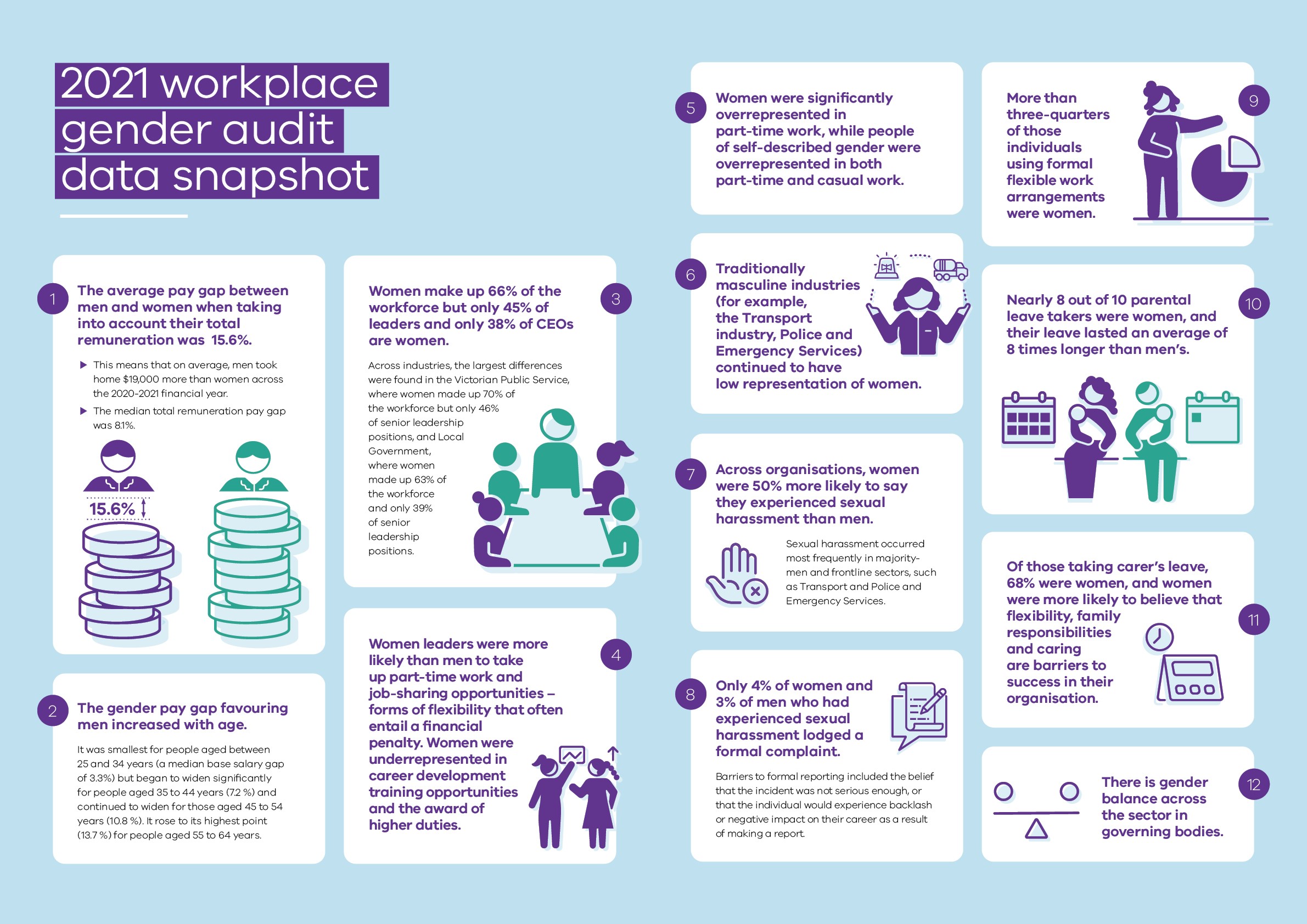

Across all the organisations covered by the Act, the average pay gap between men and women when taking into account their total remuneration was 15.6%. This means that on average, men took home $19,000 more than women across the 2020–2021 financial year. The median total remuneration pay gap was 8.1%.

In comparison, in the private sector, Australia’s national total remuneration gender pay gap was 22.8% or $25,792, as calculated by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

While it is encouraging to see organisations reporting under the Act doing better than the private sector when it comes to equal remuneration, there is still a very significant gap to close. Pay gaps existed in favour of men across all occupational groups (except at the CEO level) among defined entities. This supports existing research that the constellation of gender inequalities and biases that combine to create the gender pay gap operate across different jobs and is not a result of stereotypically ‘masculine’ occupations alone.

Part-time work

Women experienced strong representation across organisations covered by the Act, comprising 66% of all employees. However, this representation masks persistent inequalities. Most notably, when we drilled down into employment type, significant imbalances emerged. Women were significantly overrepresented in part-time work, while people of self-described gender were overrepresented in both part-time and casual work. Traditionally masculine industries (for example, the Transport industry, Police and Emergency Services) continued to have low representation of women.

Leadership

While women comprised 66% of the total workforce, only 45% of those in senior leadership roles were women and more than 3 in 5 CEOs were men. Women were also underrepresented in career development opportunities, training, and the award of higher duties.

Encouragingly, there was a gender balance between men and women on the boards of defined entities, which has been supported through Victorian Government targets introduced in 2015.

Sexual harassment

Across defined entities, women were 50% more likely to say they experienced sexual harassment than men. Sexual harassment occurred most frequently in majority-men and frontline sectors, such as Transport and Police and Emergency Services. Lack of formal reporting is a significant issue, with only 4% of women and 3% of men who had experienced sexual harassment lodging a formal complaint.

The Commission received data relating to formal sexual harassment complaints from less than two-thirds of organisations covered under the Act. Among those organisations that submitted information on formal reports of sexual harassment, there remained significant data gaps. These included a lack of data about the complainant’s relationship to the organisation, the outcomes of complaints, and complainants’ satisfaction with those outcomes. This is concerning, as comprehensive reporting and data collection systems are central to addressing workplace sexual harassment.

Flexible work and caring arrangements

More than three-quarters of those individuals using formal flexible work arrangements were women. Women leaders were also more likely than men to take up part-time work and job-sharing opportunities – forms of flexibility that often entail a financial penalty.

Nearly 8 out of 10 parental leave takers were women, and their leave lasted an average of 8 times longer than men’s.

Of those taking carer’s leave, 68% were women, and women were more likely to believe that flexibility, family responsibilities and caring are barriers to success in their organisation.

Taken together, these findings suggest that increasing men’s uptake of flexible working options and leave to care for children or others will have a significant positive impact on gender equality at work and in the home, and on women’s ability to participate equally in paid employment.

Summary of recommendations

|

Chapter |

Recommendation |

|

Chapter 1: Workforce gender composition and segregation |

Recommendation 1.1: Regular collection, analysis and reporting of accurate gender-disaggregated trend data on workforce composition is essential to improve workplace gender equality |

|

Recommendation 1.2: Build capability to effectively and safely collect intersectional workforce composition data |

|

|

Recommendation 1.3: Collect further data to help your organisation understand how forms of workplace discrimination might impact on workforce composition, occupational segregation and leadership opportunities |

|

|

Chapter 2: Equal pay |

Recommendation 2.1: Undertake organisation-wide, by-level and like-for-like pay gap analyses at least annually |

|

Recommendation 2.2: Assess all the factors identified as legitimate causes of pay variation for potential bias |

|

|

Recommendation 2.3: Invest in the development of workforce and system capability to create links between pay auditing and pay-related practices and decisions |

|

|

Recommendation 2.4: Invest in data collection systems that allow for more granular intersectional gender pay gaps to be measured and addressed |

|

|

Chapter 3: Workplace sexual harassment |

Recommendation 3.1: Collect and monitor both data that provides insight into the number of formal sexual harassment allegations and their characteristics, as well as anonymous survey data in relation to unreported experiences of sexual harassment |

|

Recommendation 3.2: Collect data on informal, as well as formal, workplace sexual harassment complaints |

|

|

Recommendation 3.3: Collect data about the experiences of people with intersectional attributes who report sexual harassment in the workplace |

|

|

Recommendation 3.4: Collect data on efforts to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace |

|

|

Chapter 4: Recruitment and promotion practices |

Recommendation 4.1: Embed gender equality data collection across recruitment, selection and onboarding processes |

|

Recommendation 4.2: Improve data collection about formal and informal career development and training opportunities, particularly for intersectional cohorts |

|

|

Chapter 5: Leave and flexible work |

Recommendation 5.1: Monitor both formal and informal flexible work arrangements, as well as feedback about how to improve uptake from employees, managers and executives |

References

- L Ryan et al., Laying the Foundation for Gender Equality in the Public Sector in Victoria: Final Project Report, University of Melbourne, 2022.

- M Cowper-Coles et al., Bridging the Gap? An analysis of gender pay gap reporting in six countries, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- For the first time under Australian gender equality reporting legislation, organisations covered by the Act were required to provide data disaggregated not only by gender, but across a range of attributes. As outlined in the Introduction, the Commission will publish insights from this intersectional data in a companion report on intersectionality, to be released in 2023.

Updated